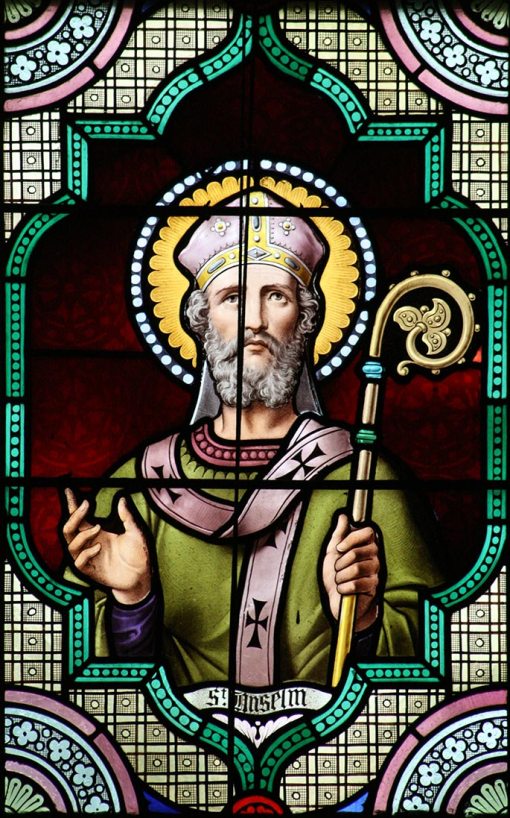

The son of a spendthrift Lombard nobleman with whom he quarrelled as a young man, Anselm was born at Aosta in the Italian Alps around 1033 and took monastic vows in 1060 at the Abbey of Bec in Normandy. He succeeded his teacher Lanfranc as prior in 1063 and Herluin, the founder of Bec, as abbot in 1078. As abbot he showed himself a capable spiritual director, his intuitive, sensitive mind well suited to the care of his monks. He succeeded Lanfranc as archbishop of Canterbury in 1093, four years after Lanfranc’s death, because the English king William Rufus (William the Second) kept the primatial see vacant for that time, despite the wish of the English clergy to have Anselm succeed earlier. Anselm’s episcopate was stormy, in continual conflict with the crown over the rights and freedom of the English Church, particularly in the matter of the investiture of bishops and clergy. He suffered exile twice because of his conflicts with King William and his successor, King Henry the First. Although he was not conspicuous for his political skill, Anselm secured a wider recognition for the primacy of the see of Canterbury, with the Church in Wales, Ireland, and (with some important reservations) Scotland acknowledging the primacy, while York also had to accept a papal decision favorable to Anselm and the see of Canterbury. Among his other accomplishments as archbishop, he held councils which insisted on stricter observance of clerical celibacy, and he established a new episcopal see at Ely.

During 1077-8, Anselm wrote the Monologion and the Proslogion. The latter work has been famous for centuries for its “ontological argument” for the existence of God. The work demonstrated the originality of Anselm’s thought and prepared the way for his later theological works. God, writes Anselm, “is greater than which nothing greater can be thought.” Even the fool, who in Psalm 14 says in his heart, “There is no God”, must have an idea of God in his mind, the concept of an unconditional being (ontos) that which nothing greater can be conceived, otherwise he would not be able to speak of “God” at all. And so this something, “God”, must exist outside the mind as well, because if he did not, he would not in fact be that that which nothing greater can be thought. Since the greatest thing that can be thought must have existence as one of its properties, Anselm asserts, “God” can be said to exist in reality as well as in the intellect, but is not dependent upon the material world for verification. To some, the ontological argument has seemed mere deductive rationalism; to others it has the merit of showing at least that faith in God need not be contrary to human reason.

Anselm’s important treatise on the Incarnation, Cur Deus Homo? was written after he returned to England from his first exile. The work is famous for its exposition of the “satisfaction theory” of the atonement, in which Anselm explains the work of Christ in terms of the feudal society of his day. If a vassal break his bond, he has to atone for this to his lord. Likewise, sin violates a person’s bond with God, the supreme Lord, and atonement or satisfaction must be made. We are of ourselves incapable of making this satisfaction, because God is perfect and we are not. Therefore, God himself has saved us, becoming perfect Man in Christ, so that a perfect life could be offered on the Cross in satisfaction for sin.

Undergirding Anselm’s theology is a profound piety, best summarized as “faith seeking understanding”. He writes, “I do not seek to understand that I may believe, but I believe in order that I may understand (credo ut intelligam). For this, too, I believe, that unless I first believe, I shall not understand.” This understanding of the relationship of prior faith and subsequent knowledge received new emphasis in the work of several late twentieth century theologians and philosophers both of religion and science.

Anselm died on April 21, 1109. The Canterbury calendar of c. 1165 provides the earliest known evidence for his feasts, one of them commemorating his death and the other his translation (April 7).

prepared from The Oxford Dictionary of Saints

and Lesser Feasts and Fasts (1980)

The Collect

Almighty God, you raised up your servant Anselm to teach the Church of his day to understand its faith in your eternal Being, perfect justice, and saving mercy: Provide your Church in every age with devout and learned scholars and teachers, that we may be able to give a reason for the hope that is in us; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, on God, for ever and ever. Amen.

_____________________________________________________________________

The propers for the commemoration of Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, are published on the Lectionary page website.